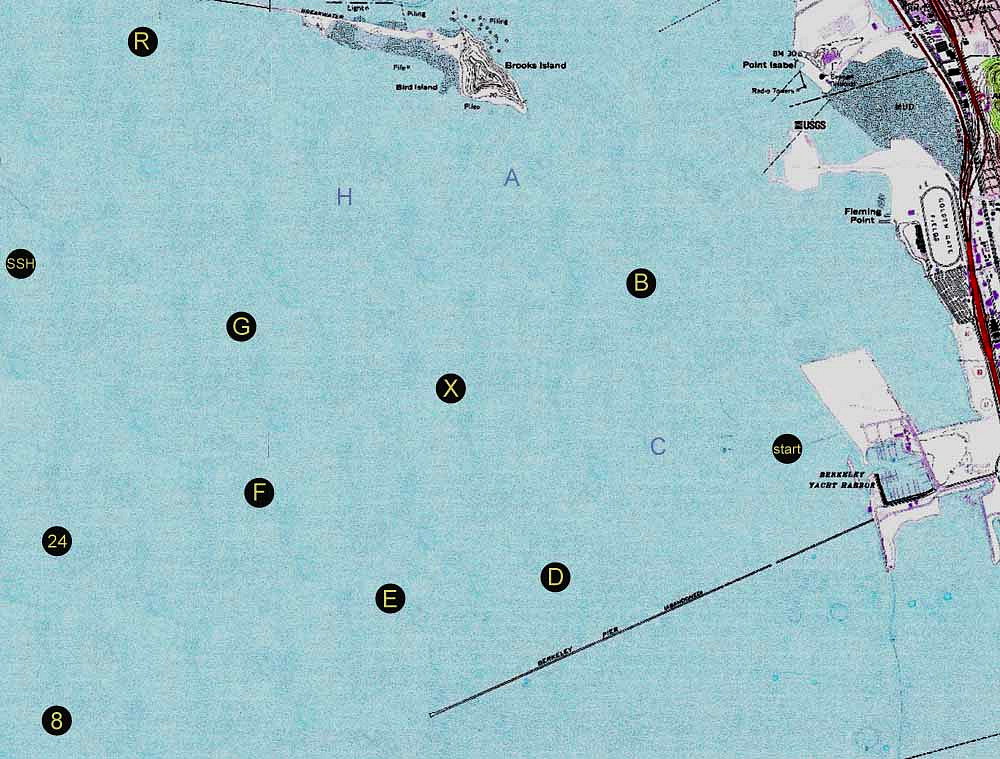

The Olympic Circle

On San Francisco Bay the best patch of water for championship racing lies on the eastern reach of the bay, an area relatively shallow and relatively tide-protected, free of the narrow rivers of current and countercurrent found in deeper parts of the bay and clear of the shipping channels. Stars, 505s, Farr 40s and many, many other classes have raced for major titles on the “Olympic Circle.” .

Photo © Peter Lyons/Marine Media Alliance

Photo © Peter Lyons/Marine Media Alliance

When I say the Olympic Circle is shallow, I mean shallow enough that the 2009 world champion of the 505 class broke a mast in one race by turning turtle and sticking it. You will hear that this place is windy, but truth to tell, it is rarely so windy as that day long years ago, in an Olympic Trials competition, when the great Tom Blackaller lost a Star and declared, “I just sailed it under.” It is a fact, however, that one Star class world championship opened with a score of “sank four, recovered two.” Those were the two you could still see, mast-top-wise, after they sank.

(There also are perfectly lovely days here, but those days do not the legends make.)

You will hear the locals referring to this area, fronting the cities of Berkeley, Emeryville and Richmond, as the Olympic Circle, the Berkeley Circle, or just “the Circle.” Circle Speak is a local habit, but these are merely wordings of convenience. Yes, U.S. Olympic Trials have been sailed here, and yes, there is a kinda-sorta circle of buoys that can be used for racing, but championship courses do not use those buoys. Championship courses employ a larger field of play and can be moved north into the lee of Angel Island, for less wind, or south—directly exposed to the Golden Gate wind slot—for more wind. In championship racing you should anticipate start lines placed relatively close to the shore, with upwind legs sailed toward the Golden Gate and a weather mark placed short of the North/South shipping lane. In what you see below, north is up, and the seabreeze comes from the left. The Google map below will enlarge or scan to show you all of San Francisco Bay, with the “Circle” area on the right.

Regatta to regatta, the race committees of clubs in San Francisco Bay expect to lay courses in a seabreeze funneling in through the Golden Gate. They expect it, though they are well aware of the truism, “No matter where you go in the world, it’s never like this.”

We have all experienced the phenomenon as competitors: weather is what you get, not what you expect. But, that said, San Francisco Bay has a remarkably-reliable seabreeze, and we know very well what we expect, March to October. Inside the bay, our seabreeze comes from slightly south of west, bending from the northwest ocean breeze and then accelerating through the venturi of the Golden Gate to create a unique sub-climate, cooler than the region surrounding, highly-localized, and ideal for racing sailboats.

Try it, you’ll like it. But the average water surface temperature at the Golden Gate is 56 degrees. The seabreeze being sucked in across it has been pre-cooled by crossing a deep-churning, chilled current offshore. If you’re racing dinghies you will need that wetsuit. And if you’re racing keelboats, you just might want fleece in July.

Actually, let me rephrase that. You almost certainly will want fleece in July. (Fleece-lined foulie shorts are, personally, part of my favorite kit.)

And as you gaze upon San Francisco Bay, remember: One-sixth of all that water goes out and in, twice a day.

These are home waters to 5O5 legend Dennis Surtees, who offers this capsule look: “The Circle is subject to the same westerly as other parts of the Bay. Angel Island provides some shelter from the wind. The westerly builds during the day. While it is building, the “left” or more easterly part of the Circle gets more wind than the “right.” After the westerly is established, the right gets an advantage from a wind bend around Angel Island. So, while the wind is building, go left. Once it is established, go right. It’s not that simple, but that saves a lot of extraneous thought. Lastly, don’t forget about tidal current, approaching the weather mark.”

Fundamentally, that’s what you should know. For more detail, read on.

The basic features of racing here are:

1) As the day progresses, the breeze will change. The most frequent tendency is a right shift as the seabreeze builds. Locals tend to favor the right-hand side of this racecourse, but many a race has been won by the first boat to recognize favored conditions on the left.

2) Upwind to the west and offset to the right (north) lies Angel Island, often contributing a topographical shift and on many days making it possible for a race committee to shift a racecourse farther from the lee of the island (south), for more wind, or toward the lee (north), for less wind.

3) As the tide cycle progresses, currents change dramatically.

San Francisco Bay has strong winds and strong currents. It inspires many conversations about “local knowledge,” so it is instructive to note that national and international titles sailed on the Circle usually go to outsiders. Local knowledge cannot override the fact that the fastest, best-prepared, hardest-working sailors are the ones who win, place, or show.

My Sailing the Bay book covers the big picture of San Francisco Bay. Here is an adapted excerpt © focused on the layout of racecourses on the “Circle.”

On the Circle, expect less wind at the bottom of the course and more wind at the top—from a different direction. This is most noticeable early in the day, while the breeze is building.

The seabreeze on the Circle tends to arrive from the south-southwest and shift to the right as it builds, yielding marked differences in the wind readings at the top and bottom of the course. That is, a stronger breeze at the top mark is more to the right than a lighter breeze at the bottom mark. Should the breeze hit 25 knots, it’s a different game. That shallow East Bay water can get choppy in a flood (with wind and current together) and ugly-choppy in an ebb. Any wind-angle/velocity difference between the weather mark and the leeward mark is swallowed up as a modulation of an ongoing emergency.

A classic beat to weather on the Circle works the right-hand side of the course, the north side. Winners sometimes sail a one-tack leg. Losers too. When the Circle is working by the book, the effect of the Point Blunt Shift (Angel Island) is to give the right-hand side a double crank: a lifted angle on port followed by a header followed by a tack and a lift on starboard.

You must not underestimate the effect of current on layline.

Did I mention? You must not underestimate the effect of current on layline.

If the seabreeze is solid and strong, it will be hard to avoid the temptations of the north side of the Circle. Here are three specific situations when you ought to consider alternatives. 1) If the wind is light, especially early in the day as the seabreeze is young, the left or the middle may have the strongest wind. 2) If the course is laid toward the southern extremity of the Circle, the influence of the Angel Island/Point Blunt Shift is reduced, so the middle and left side of the course have a greater chance of being productive. 3) If the tide is just turning to slack before ebb (because the South Bay ebbs first, creating a south-north, left-right flow bending to west/upwind), the left side may offer favorable current on the weather leg.

Olympic medalist Jeff Madrigali shared his thoughts about racing on the Circle. Here’s Madro:

“If your course is on the north side of the Circle, you’re going to be dealing with the wind that bends around Point Blunt. You go for the shift on the right, but you expect the puffs to come from the left.

“The key is knowing where you want to be on the starting line, because that’s going to set you up for how you arrive at the corner, and turning the corner sets you up for approaching the weather mark.

“I like to go from the middle of the line or maybe the left. As soon as we start, sure, I’m going to go off to the right along with everybody else, but I’ve got my options open. Maybe it’s a day when you want to go all the way to the corner. Fine, but sometimes, the way to get there is to go from the left end of the line. If you start from the right-hand end, you might get to the corner first, but maybe your end of the starting line wasn’t favored, and then you’re hosed—you’re not the fleet leader, you’re blocked, you can’t tack, and you’re forced to overstand.

“Where you tack back is critical. In the corner, the wind goes right some more—you get headed—and late in the day, that right swing is even more pronounced. Then, when you come back for the mark, you get lifted on starboard tack. And the tide’s never neutral. You’re going to get pushed one way or the other. A strong ebb is going to make the layline hard to call, but the early flood is the time when it’s hardest to get around the mark. Another thing you see with laylines on the Circle—lots of times people go to the corner and come back on what looks like the layline, but then the wind goes left a bit [you expect a lift, but there are no guarantees] and they lose what they paid for over in the corner.

“It doesn’t go the same from one beat to the next. On the second or third beat, if you’re forced to take a clearing tack coming off the bottom mark, there’s a tendency to get caved in (on your next port tack) right back into the track of the boats that rounded ahead of you.

“How you play the first beat also depends on how far up you’re going. We sailed a worlds on the Circle, with a starting line that was close to Brooks Island and the weather mark very far up. The mark was also farther left than usual, and we had early starts, about noon, and an ebb tide. There was a lot of ebb coming out of the South Bay, then sweeping out toward the Gate. That South Bay ebb was really working for the left side. We’d go off that way, and it would help us, but then we’d look at the guys who had gone even farther left, and they were looking better than we were.”

Thanks, Madro. Here are three principles to believe in: 1) The higher the level of the fleet, the more likely that someone will work the middle, or the left, with success. 2) If it’s blowing 25 out of 225° on a flood current, don’t even think about it. 3) It always pays to go right, except when it pays to go left.

And—

When you gaze upon San Francisco Bay, remember, one-sixth of all that water goes out and in, twice a day. To quote another of our greats, Hank Easom—

“Slack water is a state of mind.”