Milestones and Miles: Bermuda

There were no weather briefings back in 1906, when Rudder Magazine editor Thomas Fleming Day convinced a few people to join him in testing an untested notion, namely that it makes sense to go to sea to race as amateur crews in modest craft. Or, as I put it to myself a hundred years later, that it makes no sense, but it makes grand nonsense. Compelling, grand nonsense, so let’s go.

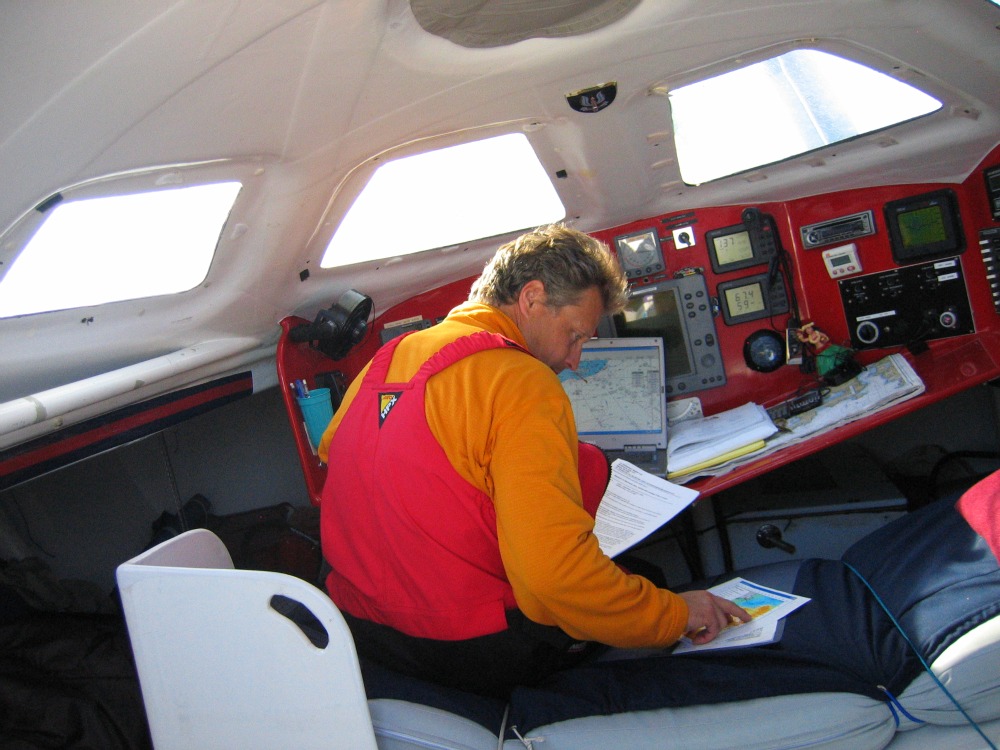

Joe Harris at the nav station of the Open 50, Gryphon Solo. Photo KL

Joe Harris at the nav station of the Open 50, Gryphon Solo. Photo KL

Following the Centennial Transpac, the Centennial Bermuda Race would be the second step in my scheme to sail milestone editions of America’s three distance classics, Transpac, Bermuda, and Chicago-Mac. The first decade of the 21st century offered that unique opportunity, and we’re about to run out of decade, and this is my recap.

The original Bermuda race went off a few months ahead of the original Transpac,both in 1906. My story would be nicely balanced, if, having sailed the one-year-early Centennial Transpac on the ultimate West Coast plastic classic, a Cal 40, I had then sailed the Centennial Bermuda on the ultimate East Coast plastic classic, a Hinckley Bermuda 40 yawl. I stand by that, though I should note: The big-show winner in the Centennial Newport-Bermuda Race, 2006, was a Cal 40 named Sinn Fein, owned by one Peter Rebovich, Sr. out of Raritan Yacht Club, New Jersey. This came after class wins in the two previous races. And Rebovich came back again in 2008 and repeated as the big-show winner. He became only the second skipper in history and the first (complete with loyal amateur crew) to win the St. David’s Lighthouse Trophy in consecutive years since the legendary Carleton Mitchell pulled it off 1956-58-60. Rebovich missed a three-peat in 2010; Carleton Mitchell stands alone.

Sinn Fein. Photo by Daniel Forster

Sinn Fein. Photo by Daniel Forster

But, apparently, our West Coast classics do OK on the Mysterious East Coast, and so far, the only person I’ve heard from who also sailed all three of the milestone editions was another left coaster, Ben Mitchell, who went maxi all the way: Transpac on Pyewacket; Bermuda on Titan; Race to Mackinac on Genuine Risk.

So we’re still not quite done with the Cal 40 thread. In the pic below, cropped from a scrapbook belonging to the fellow who imagineered the Cal 40, George Griffith, we see crew and families of Psyche, the Cal 40 that started it all and ran 1-1 in the 1965 Transpac. Standing at left is one Ben Mitchell, a celebrated navigator of his generation, and the little-little guy in front—well, that’s our generation’s Ben, the one who was out there with me, somewhere, on the Pacific, the Atlantic, and that very big lake called Michigan . . .

Come June, 2006, we were 265 boats milling around off Castle Hill, Newport, waiting for the start of a race that everybody knew would call for some gambling on the part of the navigators. We were 265 boats, a record to that point, because milestone races are like that. We’re all suckers for hundred-year anniversaries. (The 1906 Bermuda beat the 1906 Transpac by a matter of months.)

Around us were a number of offspring of Carleton Mitchell’s pace-setting yawl, Finesterre; also a few progenitors. Me, I cut my sailing teeth reading Carleton Mitchell’s accounts of cruising and racing. They seeped into me, and it’s his fault that to this day I’m queer for yawls even though they make no engineering sense. I love to look at them on the water. What was it Nathaniel Herreshoff said? That half the reason to own a boat is to look at it.

And what was it Bob Keefe said? It’s handy to have a mizzen when you need to hang a sunshade.

Carleton Mitchell’s Finisterre

Carleton Mitchell’s Finisterre

There was only one Bermuda 40, by my count, racing the Centennial Bermuda, but quite a few of her cousins were on hand. Here is the lovely Concordia, Dame of Sark, at the start line . . .

Much (much) later, after five days on the course, Dame of Sark looked just as good slipping into the harbor at Hamilton, but skipper Stephen Donovan would tell me, “We’d been six people in tight quarters, in primitive conditions, and you didn’t want to get within a hundred yards of that boat if your nose was working.”

Right. It was a slow race. And I couldn’t say that our own conditions were unprimitive. Five people, two bunks (pick a sail and cozy up), a one-burner stove on a 50-foot “yacht.” And yet, it was perfect. Joe Harris was the owner of Gryphon Solo, the Open 50 that Brad van Liew had soloed around the world as a winner under a different name. Joe had raced the boat solo to a division win in the Transat Jacque Vabre (and an overall win in the Bermuda One-Two was a year away). All carbon fiber. Canting keel. Twin daggerboards. Twin rudders. And dig that twin-tiller setup.

Joe Harris had breeze, steering Gryphon Solo at the start. (I owe somebody a credit)

Joe Harris had breeze, steering Gryphon Solo at the start. (I owe somebody a credit)

We never got to bomb that big widebody downwind, but while other off-helm crew on ordinary boats spent hours crouched on the low-side rail, nose-to an overlapping headsail, the conversation on our boat would go, “Could you give us ten degrees of negative keel?” And someone would push a button, and the keel would cant to a greater angle. The boat would heel, and most of that widebody would air-dry, leaving only a small wetted surface to push through the water. As my crewmate Jamie Haines explained, “If the wind guage is showing eight knots, the speedo should be reading seven plus.”

Simplicity is good, but when complexity works, it’s great.

Breakfast on day two was interrupted by a whale sighting. Yes, that’s, um, a doggie dish in Joe’s hand, and yes that’s a joke, sort of. But doggie dishes are designed so they can’t be knocked over, right?

Hugh and Joe on whale watch. Photo KL

Hugh and Joe on whale watch. Photo KL

With a big, heavy, high pressure system squatting on the layline, we had the option to go around to the right, via Omaha, go around to the left, via Glasgow, or go through.

We were going through.

There were no weather briefings back in 1906, when Rudder Magazine editor Thomas Fleming Day convinced a few people to join him in testing an untested notion, namely that it makes sense to go to sea to race as amateur crews in modest craft. Or, as I put it to myself a hundred years later, that it makes no sense, but it makes grand nonsense. In Day’s day no one could chart the trends in the Gulf Stream. They just knew that weather was out there, and the Stream was out there, and as Mark Twain had said, “Bermuda is paradise, but you have to go through hell to get there.”

We might have been just as well off, taking the old-fashioned approach. Instead, what sorted out for Gryphon Solo, out of reams and reams of data and hours and hours of research, was the bet that a westerly route would be favored by currents, and an easterly route would be favored by wind. Three days out, along the “wind favored” easterly route, I woke at dawn to find us becalmed becalmed becalmed—in the company of much bigger boats, including the 98-foot Maximus—and the people on those big boats could not have been happy to see us. I’m pretty sure I could make out Robbie Doyle over there on the 77-foot Langan sloop, Captivity. Joe dryly remarked, “It is reassuring to see that some of the best minds in the game made the same unfortunate choice that I did.”

Was this a chess board, in the way that we often liken sailboat racing to chess?

Or was it a bingo board?

Brian Harris and Jamie Haines working the moment. Photo KL

Brian Harris and Jamie Haines working the moment. Photo KL

None of the weather updates matched reality, so we shifted our strategy from trying to position the boat relative to predictions to simply trying to sail to Bermuda by the shortest possible track. The good news: a light breeze soon sprang up. The bad news: it came straight out of Bermuda, complicating our new strategy considerably.

At that point in a 635-mile race, the fleet was spread 150 miles, left to right. And the right was right. From over yonder, from 200 miles to go, Hap Fauth’s Bella Mente sailed a beeline to the finish and took line honors ahead of some much bigger boats. We made the finish in the wee hours, three days out and change.

Had I gone on a Bermuda 40, on the eastern route, figure two days more.

I won’t make much of the fact that we won our “Demonstration Division” for cant-keeled performance boats. Pindar Artemis put itself out by hitting a rock before the start, leaving only our 50-footer against the 98-foot Maximus, a boat that never did live up to the noisy hype of its PR team. In a light-air race the smaller boat should win, did win. But it is remarkable how a race that began long ago with what many regarded as a lunatic fringe has grown into a signature event of establishment yachting. The Cruising Club of America stepped in as 20th century ocean racing blossomed and is now the co-host of the race along with the Royal Bermuda Yacht Club. Close to 5,000 people have now participated in this classic of classics.

And a footnote often overlooked in accounts written by sailors: In 1912, Thomas Fleming Day made the first Atlantic crossing in a gasoline-powered motorboat. Yes, that was an adventure in itself.

Fair to say, the Royal Bermuda Yacht Club knows how to manage these things. This is our boat captain, Hugh Piggin, accepting the award from HRH Princess Anne . . .

And it’s sort of surprising that, early in my generation—though, obviously, no longer—it was still something to talk about when women went ocean racing. Surprising, because in the 1906 inaugural Bermuda Race, among the three boats that started and the two that finished, there was a woman involved. Yep, the 28-foot Gauntlet included in its crew, to the consternation of the critics, one Thora Lund Robinson, a dewy-eyed twenty year old and a bride to the owner of only six weeks.

Thora Lund Robinson at the helm of Gauntlet

Thora Lund Robinson at the helm of Gauntlet

They arrived behind the 38-foot yawl, Tamarlane, which had Day for a sailing master, but it was Thora who became the toast of Bermuda.

Gauntlet remains the smallest boat ever to have sailed this race. As noted by John Rousmaniere in A Berth to Bermuda, his hundred-year history of the race, “She would never pass a pre-race inspection today.”

And that, by the way, is a book you should read.

The salty fellow on the right, below, is Thomas Fleming Day, a man never weak in his opinions, nor hesitant to act upon them . . .

Thank you, Thomas Fleming Day. By and By, on to Mackinac, as occasion serves.