American in Paris, Not

At the National Maritime Museum, Paris

At the National Maritime Museum, Paris

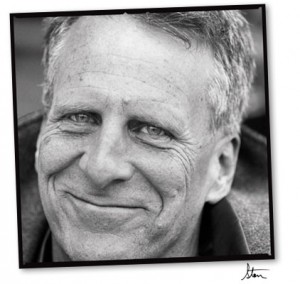

Stan Honey’s status as the navigator of the fastest-ever circumnavigation is safe.

For a while.

A broken Banque Populaire V is even now sailing back to France—a nighttime collision damaged a daggerboard beyond repair, just as the boat was approaching an entry point to the Southern Ocean—and there will be no one threatening Groupama 3‘s 48-day round-the-world record when Stan Honey is honored as Rolex US Yachtsman of the Year in New York City on February 25.

But, talk to Stan about the boatride that secured the Trophée Jules Verne and you’ll discover that it was a cultural experience as well as a sailing experience. He was, after all, the only American in the crew, the lone Yank surrounded by the “Brittany mafia” as he calls them.

“In France,” Honey says, “professional sailing works in a healthy and sensible way that we are not familiar with in this country. You have sponsors that come into the game and stay, because it works for them. Groupama is an international insurance group headquartered in Paris, and they have had a special relationship with Franck Cammas for going on sixteen years. There’s a budget of $20 million or so every year, and Cammas has as many as four projects going on at a time. Franck has two giant buildings in Lorient, naval architects, a construction crew—and I talked to his sponsors, and I asked what they like about this, and yes they like the internet hits and the magazine stories, but what they really like is the venue-based entertainment. Very much like NASCAR. ”

And life aboard a 105-foot trimaran on a mission to set a record around the world?

“I’ve sailed a lot with Kiwis, and the obvious difference with the French is the food. The Kiwi way of working with dehydrated food is to dump all the powder into an insulated pot, pour in a few quarts of hot water, stir it with a winch handle, and call it done. You get the same meal every eight hours. There’s never a ‘breakfast,’ never a ‘dinner.’ By the time you’ve finished a lap of the world on a Kiwi boat you don’t want to ever see freeze-drieds again. The French? Well, the French take pride in their cooking, and even if it’s freeze-drieds they’ll have a couple of pots working, do up some noodles, a dash of olive oil, it really makes a difference. We carried dried hams from Spain, cheeses that last, and there’s a baker in Brittany who has been triple-baking bread for sailors for generations. Big, flat loaves that are good for, well, forever. We had that bread for a month, with no mold and no special care. They were just piled up like crispies.

“I’ve sailed a lot with Kiwis, and the obvious difference with the French is the food. The Kiwi way of working with dehydrated food is to dump all the powder into an insulated pot, pour in a few quarts of hot water, stir it with a winch handle, and call it done. You get the same meal every eight hours. There’s never a ‘breakfast,’ never a ‘dinner.’ By the time you’ve finished a lap of the world on a Kiwi boat you don’t want to ever see freeze-drieds again. The French? Well, the French take pride in their cooking, and even if it’s freeze-drieds they’ll have a couple of pots working, do up some noodles, a dash of olive oil, it really makes a difference. We carried dried hams from Spain, cheeses that last, and there’s a baker in Brittany who has been triple-baking bread for sailors for generations. Big, flat loaves that are good for, well, forever. We had that bread for a month, with no mold and no special care. They were just piled up like crispies.

“And, on a Kiwi boat, it’s considered bad form to look over the shoulder of the navigator and offer suggestions. On a French boat, there is always someone looking over your shoulder, and I did get a bit more advice than I’m used to.”

So why an American navigator on a French boat?

“I asked Franck about that, and his concern was that his French guys, coming out of shorthanded sailing, tend to take a quick and dirty approach. He wanted the boat to be navigated the way a Volvo Ocean Race is navigated, where you have a full-time person who’s making every last risk assessment, trying to get everything exactly right, leaving nothing on the table. It was an honor to sail in that community, and they were very supportive.

“Franck’s sailors are jack-of-all-trades, mechanics, navigators, sailmakers, electricians, riggers, and for shorthanded competition they’ve had to incorporate the concept of triage, that you cannot get everything right all the time. You have to decide what’s most important and take care of that, and take care of yourself. Get rest. Stay dry. They bring that sensibility to offshore sailing. Groupama 3 was properly, I could even say, cleverly, rigged, and they had gone to a great deal of trouble to make sure that it stays dry belowdecks. The experience could not be more different from a Volvo Race, where there’s water sloshing around constantly and you’re always bailing and you’re always cold and wet.”

[Honey navigated ABN AMRO ONE to a win in the 2005-06 Volvo Ocean Race.]

“On Groupama 3 the traveler and the gennaker sheet were hand-held, all the way around the world. People ask if I worried about flipping the boat, and the answer is, not really, not with some of the best sailors in the world hands-on. The other side of that is, Franck is prepping now for the next Volvo Race, which he says is much harder but less stressful than the Jules Verne trip. When I pushed him on that, he said, in a Volvo boat what’s the worst that can happen? Maybe you get knocked down and the boat is on its side and you have a mess. With a big multihull the worst that can happen is you go upside down and maybe lose the boat. Franck has a unique perspective on that because he has capsized more large, offshore multihulls than any other human.”

Yes, and he flipped Groupama 3 on a previous attempt at a Jules Verne record, so we know it can be done. What about your watch system?

“We had ten guys and three watches. It was three on, three off, three on standby, suited up. I was on standby all the time, whether I was navigating or asleep. I was on deck for every maneuver we made, all the way around the world. But when there was nothing much going on I was free to just navigate. They guys were very cool about it. They were always offering me a trick at the wheel, but I couldn’t spend much time there without starting to think that I wasn’t adding to the performance of the boat, that if I stood there steering for too long I could be missing something as a navigator.”

“We had ten guys and three watches. It was three on, three off, three on standby, suited up. I was on standby all the time, whether I was navigating or asleep. I was on deck for every maneuver we made, all the way around the world. But when there was nothing much going on I was free to just navigate. They guys were very cool about it. They were always offering me a trick at the wheel, but I couldn’t spend much time there without starting to think that I wasn’t adding to the performance of the boat, that if I stood there steering for too long I could be missing something as a navigator.”

On a boat that large, averaging 24.74 knots through the water for 28,691 miles, what is the conversation about safety?

“Everybody carries a knife, and everybody is experienced at cutting through the trampoline in case of capsize, but nobody wants to experience that. We carried life rafts—in case of fire—but there was one safety feature I liked a lot. In case of an overboard, the GPS emergency button that you would push to mark the spot was keyed to also pneumatically release the overboard gear. Push that button and your buoy hits the water instantly. We did a whole day of drills, and in most cases the gear dropped right beside the person in the water. That is so much better than expecting someone to run and pull a pin and you’ll be who knows how far away when the gear hits the water. There is no such thing as a quickstop in one of these boats. You have to furl and reef, and you’ll probably be coming back from two miles away. ”