Ducks Have Right of Way

Moody ducks, but that’s not what we’re talking about. Photo by Dave Kneale

There is more than one way to approach the game of yacht racing.

I figure every one of them has value.

I figure every one of them matters.

You can go aspirational. It’s about climbing the ladder. Winning an Olympic medal, perhaps, or winning a class championship, or winning the season on your local pond, or just getting through a regatta with top-half finishes in every race. You get to define “winning.” That belongs to you. But you’d better be keeping a journal, taking notes, following the example of Dennis Conner and leaving yourself “no excuse to lose.” Whether you’re sitting on carbon fiber or plywood, twitching a tiller or trimming a sheet—or hiking hard, hoping to eventually get to move up to being a trimmer—it is a fine thing to be obsessed with sailboat racing.

Needless to say, Antoine Screve and James Moody, two young Americans who just won the 29er sailing at the Volvo Youth Sailing ISAF Worlds in Istanbul, are living, sleeping, waking in that mode. That would be Screve and Moody in the picture at the top of this story.

But you could also say to yourself, it’s a lovely day on the water, and it’s more fun to be out here if we’re playing a game, and while we play the game we try very hard, but we know it’s all horsefeathers, so who cares how it comes out.

Take away either mode, and as a sport, we lose.

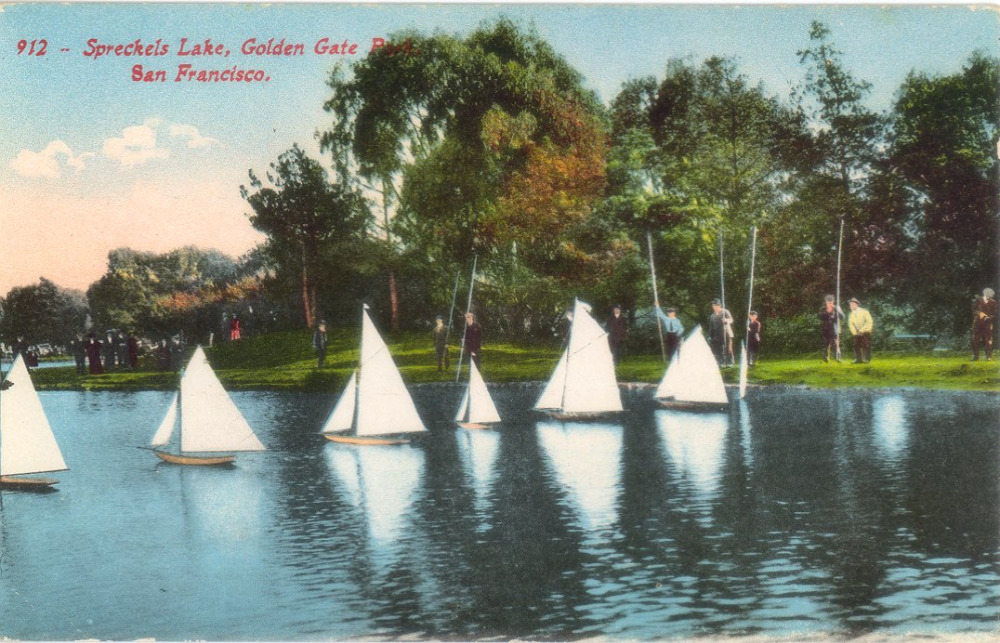

I got to thinking about the difference while I watched X-Class models race on Spreckels Lake, Golden Gate Park. This is the only place in the USA with a fully-commissioned free-sail fleet. Meaning, racing in the old way, without radio control, and the differences between free-sail and radio control are huge.

Radio-controlled competition uses Appendix E of the Racing Rules of Sailing, which makes only a few changes to the rest of the book. I’ve watched people get pretty wound up in the middle of a models race, same as they do in what the model sailors call “people boats.”

Passion rules, but ducks have right of way.

(btw, a few years ago I wrote a feature, Pond Life, for SAIL Magazine, and it drew the biggest response I’ve ever had to a magazine story. This model stuff is serious. Further btw, 2010 is the 40th anniversary of the American Model Yachting Association. Happy birthday.)

Free-sail competition deserves a bit of explanation.

Spreckels Lake was purpose-built in 1903, with the north shore of the lake running parallel to the seabreeze. The same reliable, westerly seabreeze that gives San Francisco Bay its sporting character. There is just a minor curvature to the north shore, to please the eye, and having a shoreline parallel to the prevailing wind is what makes free-sailing here a pleasure. Races start downwind, go the length of the lake, and return. The art and science—it takes both—is to tune your boat slightly out of balance, so that it will sail itself out into the lake, far enough but not too far, lose balance, turn, and sail back to the shore.

Your job, downwind and back, is to walk along and meet your boat. You carry a 5-foot, 4-inch stick, and you are allowed to touch the bow once, to turn the boat back into the lake, and your are allowed one course-correction touch to the stern. Two boats race together. Anything more would be mayhem, but there usually are multiple races under way.

At the bottom of the course you take your boat in hand and reset the sails to tack upwind. Each race is thus two races in one. If you split, the upwind-leg winner takes the tie break.

Occasionally you see a boat that isn’t set up quite right, sail off toward oblivion.

Occasionally you see a grown man run.

And make adjustments.

What I’ve never seen is a free-sail competitor yelling. The yachts are each a thing of beauty, restful to the senses, and yes, some boats are faster than others, and some skippers are more skilled than others, and fast boats and smart skippers are likely to come up winners.

But.

That wonderful, celebrated seabreeze that blows in as reliably as ever is all chopped up these days by the forest that has grown up in Golden Gate Park since the lake was created. Think random puffs. Random shifts. A fickle finger of fate always ready to stick it to you.

You must be at peace with the fundamental absurdity of the game.

May it always be so, and so lovely.

The San Francisco Model Yacht Club dates to 1898 and these days occupies a WPA-built clubhouse at Spreckels Lake where the members not only preserve the treasures of the past but also keep them trim and active.

POWERBOATS TOO, AND STEAM

The powerboat side of the Model Yacht Club gets the south shore of the lake for their fun and games, and the club’s second annual Steam Up on Sunday, August 8 from 1000 to 1600 will be a delight. If you’ve never seen a steam-powered six-footer, exquisitely detailed and puffing proudly along, your karma is not complete.

The powerboat side of the Model Yacht Club gets the south shore of the lake for their fun and games, and the club’s second annual Steam Up on Sunday, August 8 from 1000 to 1600 will be a delight. If you’ve never seen a steam-powered six-footer, exquisitely detailed and puffing proudly along, your karma is not complete.

Full disclosure: Dress warmly. The marine layer is 2,000 feet thick.

Spreckels Lake is on the western, seaward side of San Francisco, and I happen to live on the western side of San Francisco, and just at the moment, in my sentient, front-of-computer mode, I’m wearing two layers of fleece over a wool sweater. You photographers will have noticed there were no, ah, highlights in my photographs of the X-Class.

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SIWASH

The one hundredth birthday of what we believe to be the oldest still-active boat in Southern California was duly celebrated last weekend at Los Angeles Yacht Club’s Catalina cove, Howland’s Landing.

Friends and family turned out . . .

Owners Bill Wright and Deborah Bird were in fine form . . .

Among the many well wishers was George Griffith—the man who long ago envisioned the Cal 40 and made it a reality, and changed the course of boat design—dropping by to pay his respects . . .

It is special to see one boat in one family for 99 of its first 100 years. We told the Siwash story in this earlier post.

My thanks for the photographs go to Fin Beven and to Walter Savage Wright’s descendant, Heidi Fuller. It was Walter Savage Wright who bought the boat in 1911, for his son, and set Siwash on her way. He couldn’t possibly have imagined.