Milestones and Miles: The 100th Mac

I love Chicago for the sheer vertical audacity of it.

An astounding (why here, but why not here?) confluence of energies sets this place apart. And when I flew in for the 100th running of Chicago-Mac, the place was alive. Summer was on. In Millennium Park, the whole world was out . . .

At night, the ever-changing images on the twin monoliths, reflected in the wading pool, continue to fascinate . . .

I was on the final leg of my mission to sail milestone editions of America’s three distance classics: Centennial Bermuda, Centennial Transpac, the 100th running of the Race to Mackinac. The opening decade of the 21st century offered that unique opportunity. Now the decade is winding down, and this is my report.

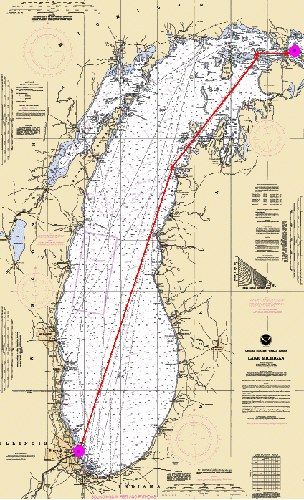

I sailed Transpac ’05 on a Cal 40. I sailed Bermuda ’06 on an Open 50. The final leg would be Mac ’08 on a J/122 for a grand total of 333 rated miles, which is kinda sorta far, except that I have friends who do circumnavigations where that mileage is nothing. And of these distance classics, the Race to Mackinac is the shortest, but it most revels in how hard the race can be—most of the length of Lake Michigan, Chicago to Mackinac Island, 333 miles. This signature event of Chicago Yacht Club has been raced almost-annually since 1898.

I sailed Transpac ’05 on a Cal 40. I sailed Bermuda ’06 on an Open 50. The final leg would be Mac ’08 on a J/122 for a grand total of 333 rated miles, which is kinda sorta far, except that I have friends who do circumnavigations where that mileage is nothing. And of these distance classics, the Race to Mackinac is the shortest, but it most revels in how hard the race can be—most of the length of Lake Michigan, Chicago to Mackinac Island, 333 miles. This signature event of Chicago Yacht Club has been raced almost-annually since 1898.

If you’re a sailor hereabouts you have to go. Youngsters scouting the docks will ask, “Are you going to Mac?” If the answer is, No, they keep walking.

It’s a cult thing. When you’ve racked up 25 races, you qualify to join the Island Goats Sailing Society, an organization that refers to the experience via these pithy active verbs (their words, not mine): endured, survived, suffered.

I get it. When the wind switches off, the flies arrive. For a while in ’08 we even had a bat in the rigging. And I’ve never before seen that much lightning from the deck of a boat.

But it’s also so damned beautiful.

It occurs to me that I sailed the 50th Ensenada Race, back in the day, and in the spring of 2008 I was on my way to Mobile Bay for the 50th Dauphin Island Race when I was benched by strep. Milestone event is to journo as flame is to moth. If you’re a sailor in the bargain, it’s all the excuse you need.

Rich Stearns was our core player aboard Bill Zeiler’s J/122, Skye—in 2009 and again in 2010 Bill and Rich teamed up to win the doublehanded division—and Stearns explains the Mac as not one race, but four races back to back, through changing geographic zones. This was my second Mac (23 to go) and I’ve built up the conviction that it’s not so hard to win. You just have to be fast enough and smart enough and work hard enough to deserve it; then you need to get lucky several times in a row.

Rich and Lori Stearns live in an apartment high above South Michigan Avenue, and from that lofty height we observed, not much. Enough to confirm that it was pointless to go early to the boat and explore up the course. Something about the rain (in plenty) and the visibility (not so much). The wetness backed off for our start, but we went the first two days of the race without seeing sun, moon, stars. I have never before or since been on the water with so little visibility and so many boats, a record 433 or something such. We encountered some bogies, but even so, only one that was metabolism-altering, and we were the ones who got to yell Starboard and watch the other guys scramblescrum to gybe their spin. Here’s Bill driving on the morning of day two . . .

Generally, the bogies that appeared out of the vapor were on the order of GL70s, TP52s, and other big things whose crews must have been throroughly PO’d at the sight of our stock-but-not-slow 40-foot J.

Turning Point Betsy, the race transitioned out of the open lake and into the Manitou Passage. There, true to Rich Stearns’ prediction, boats appeared all around us as the on-deck murk cleared to an overhead cover. This was my second Mac, but for Bill Zeiler, it was number 25, his qualifier as an official Island Goat.

Hallelujah to the arrival of a tiny sparrow, or near-cousin. He landed right behind a wave of biting flies and made counterclockwise circuits of the deck, chomping bugs. He had no fear. We named him Scrappy Skye. I snapped this just before he hopped onto Zeiler’s hand to nab that pesky (tasty) fly . . .

The arrival of a bat was a first for me on a boat. We rousted him from the mainsail, but he came right back and clung to the mast until we went into a sequence of back-to-back gybes and spinnaker peels that probably came across like the battle of Midway. The thing about sailing with Rich Stearns (J/Boats Midwest) is that he’s an affable, genial Type A. Never any stress, always with a sense of detached humor regarding this crazy obsession for making a slow object advance through the water expeditiously. He’ll invoke the five-minute rule on a shift of the breeze, then 90 seconds later he’s going for it. Also along, but not just along for the ride, was Rich’s Dad, Dick Stearns, one of the legends of the Lakes, one of the legends of the Star class, one of the legends of American sailing, period. When a younger crew asked for a sailing lesson, Dick said, “Just close your eyes and feel the boat.”

When Rich asked his old man, as a half-hour ticked down, “Ready for a spell on the helm?” The response was a glance at a watch and, “Not for another 2 minutes and 43 seconds I’m not.” Shot almost at that instant . . .

Meanwhile, why would anybody sleep in a bunk if you might shave seconds off your course time by sleeping on the rail?

On day three, we passed under the Mackinac Bridge, the transition to the short-final “race four,” mere hours in advance of a nasty cold front. Here we have Lori, a bit of competition, and the bridge . . .

Now, let me tell you, this thing that I do, writing about sailing, can get a little crazy. Most of the time I write from a home office above the Golden Gate Strait, two miles seaward of my own special bridge. I’ve also scribbled in notebooks while gripping a penlight in my teeth, and I once spent $3,200 of the San Francisco Chronicle’s money—in 1981 dollars—radio-telephoning stories from a Class A Transpac ride (hey, we won our division). I’ve worked in bars. I’ve worked in airports. But the morning after Skye arrived at Mackinac was frantic. These island people do their best to hurry their sailor guests along in order to return the island to its proper serenity. Mackinac Island is an auto-free zone, and this is the flavor . . .

So Chicago Yacht Club starts its awards ceremony in the morning on day four. In the 100th Mac, that left a passle of boats still at sea as Bill Zeiler, with his family and (most of) his crew, accepted his section award . . .

I made it, but no way was that guaranteed. I have a friend who claims to have photographic evidence that I was in the Pink Pony at 0300 the night before, but she has failed to produce said evidence, so I declare the claim spurious and refuted. Nonetheless, it was a challenge to roll out on Central Time, patch together an online story, and dash heck-for-leather to a morning awards ceremony. Especially since I could not not not make the hotel’s wifi work for me. A call to Bill Zeiler—if he’s done 25 Macs, he’s not without connections—led me to the hotel desk where they put me behind the counter at one of their own computer stations. And there, in full view of a jampacked lobby, as I waved off friends, some of whom I hadn’t even howdy’d up, I put out a story out in a fever of flying fingers. I read it through for glaring typos. Good enough. Hit SEND. Dashed blind to the prizegiving.

Later, I discovered that I had tapped into words that speak to why I do this, why we do this. The frenzied passage below still works for me. In the opening decade of the 21st century I made my milestones, and—

I had awakened in the morning with a great sense of well-being. I’m good with the sound of a rushing bow wave. But as we flowed on through the mist I fell to remembering that I’d just the night before had word from a friend out West that Mark Rudiger had lost his fight with lymphoma, and I remembered Paul Cayard now at sea with his family on the Pacific Cup and how fine it is that this giant of grand prix racing has seized the opportunity to sail with his kids and their friends at a special, unrepeatable time in their lives and I have so many other friends also on the high Pacific right now, some of them alone in the solo Transpac but not alone because they yak it up every day on the SSB so they have “family” too, and all these miles pass under so many keels—and Rudiger navigated Cayard’s round-the-world race win—and there are so many friends from all over that I’m running into here on the streets and last night the rain was bitter cold on Mackinac Island and most of the fleet was still out on the course and g’bless’em and now it’s morning and I’m writing and boats are still coming in and time slips away from us and there is a sad beauty to that which seems to come directly out of this ephemeral, lovely thing that we do with water and boats and wakes that appear and disappear and there is no way to finish this sentence, no way to begin. The sailing life is a good life. Thanks, Mark. Damn.

.

.

.