Milestones and Miles

In the opening decade of the 21st century I had the opportunity to sail milestone editions of America’s three great distance classics: Centennial Bermuda, Centennial Transpac, and the 100th running of Chicago-Mac.

So I did.

If anyone else did the same, I’d be interested to hear. Along the way I got fried, frozen, slammed, sore and high on sailing and life. I lost one friend and made others. I sailed the Centennial Transpac on the ultimate West Coast plastic classic, a Cal 40, and the story would be nicely balanced if I had then sailed the Centennial Bermuda on the ultimate East Coast plastic classic, a Hinckley Bermuda 40 yawl. But I am so glad I didn’t. And, I had sailed the Race to Mackinac before, so this time I was spared the ritual dunking—that water’s cold, baby—at the other end.

The bare facts: First race to Bermuda, 1906. First race to Honolulu, also 1906. First Chicago-Mackinac, 1898, so I missed that Centennial, but accounting for a few gaps during wartime, the 100th edition came up in 2008. Much of what we know in the sport today was getting off the ground in the first decade of the 20th century. The first international rule. The first international authority. Milestone editions of the great distance classics were obvious attractions for a journo, with organizers heating the oven just a little bit hotter and more boats and more people showing up for the special occasion.

The first twist in my tale occurs, ironically, in 1936. Because—

In 1936 one Jim Flood of San Francisco, California was the new owner of the most famous racing yacht in the world, Dorade, brought out from the Atlantic coast to see what Olin Stephens’ remarkable yawl could do in the Transpacific Yacht Race, Los Angeles to Honolulu. Flood wisely secured Myron Spaulding—designer, builder, measurer and violinist—as sailing master for a race that got off to an excruciatingly slow start. Thirteen days later, however, Dorade bombed down the Molokai Channel past Diamond Head with the first sweep in the history of this biennial classic. That is, since race one in 1906, no boat had previously been first to finish, first overall on corrected time, first in class. It wouldn’t happen again until Windward Passage pulled it off with a brilliant win in 1971.

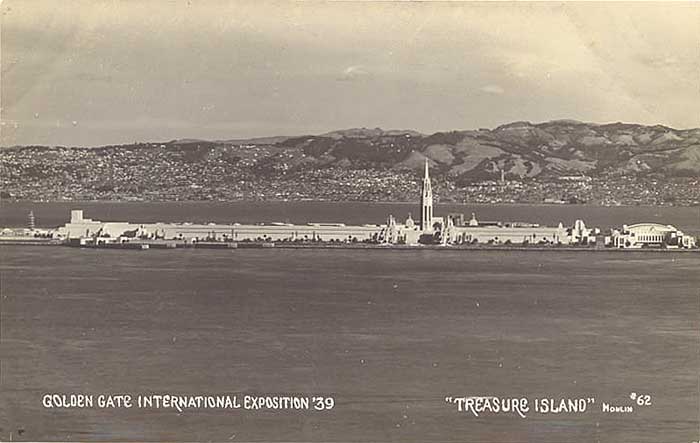

Mind you, Jim Flood was an influential man. Inheriting a silver-mining fortune and a marble mansion on Broadway can go a long way to help with that. And suddenly he was an influential man inside the Transpacific Yacht Club. Flood proposed to start the next race from San Francisco Bay to coincide with the 1939 Golden Gate International Exposition. Among the consequences would be a three-year gap instead of two, but it is easy to imagine the man arguing the benefits of assembling the next Pacific fleet under the eyes of an international audience. And switching to an odd-numbered year would open the possibility of attracting boats from the Atlantic coast that might otherwise stay home to race to Bermuda.

Flood prevailed, and the 1939 Transpac started from manmade Treasure Island, in San Francisco Bay.

(The Expo proved a great success, though less international than imagined. War had already begun in Europe. The race did succeed in attracting one boat from the Mysterious East Coast, R.J. Reynolds’ 55-foot S&S cutter, Blitzen, which had won everything it touched back East, and then won Transpac, too.)

Many years on and with 2006 approaching, a new Transpac YC Board had to decide. Since we can’t hit 2006 on the head without upsetting the applecart, do we go one year early or one year late for the Centennial celebration. The decision: Go one year early, 2005.

Which kinda sorta jumped the gun on Bermuda, but—

Events leading to my Centennial Transpac began in Southern California in the early 1960s with a fellow named George Griffith, now Transpac YC member #1 (“It means I’ve lost a lot of friends”) and known as the godfather of the Cal 40, the most influential boat of the second half of the Transpac century.

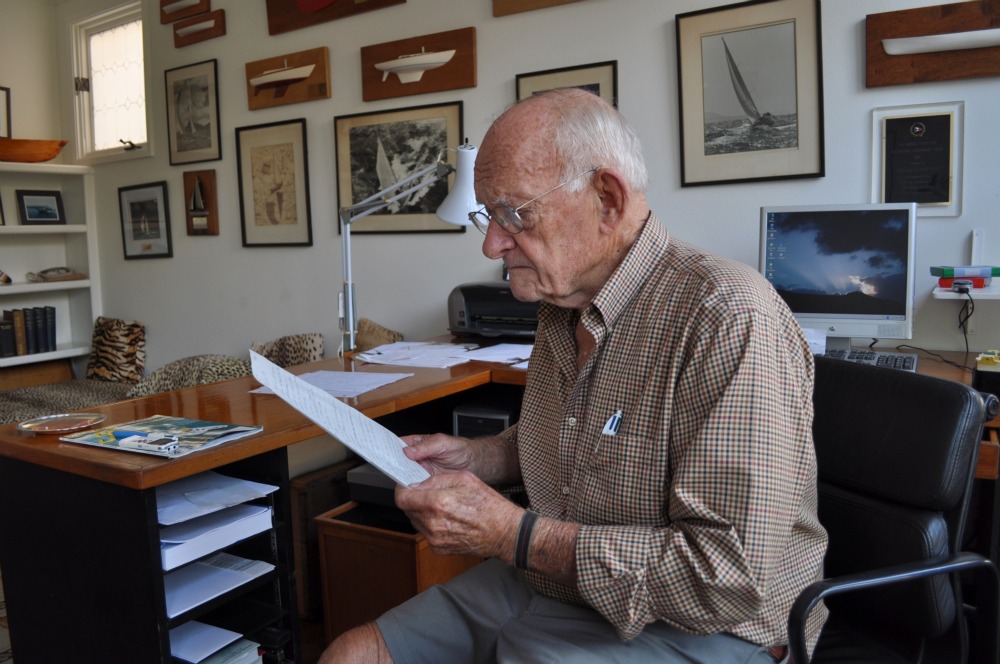

George Griffith in his Long Beach home/office, 2010. Photo KL

George Griffith in his Long Beach home/office, 2010. Photo KL

Sure, Bill Lapworth did the naval architecture, but Griffith sketched the midsection that defined the ride, and he specified the fin keel/spade rudder layout on a then radically-light structure and talked the people around him into believing in it. Then, in the 1965 Transpac, Cal 40s ran 1-1 and 2-2 and four more Cal 40s placed in the top ten overall. We’re talkin’ revolution.

George’s scrapbook: An exultant Psyche crew, 1965. George is far right in the crew photo. Far left in both B&W photos is one of the great navigators of his generation, Ben Mitchell. His son, Ben, is the littlest kid in the B&W at bottom. In a Comment below, Ben writes that he sailed the three milestone races: Transpac on Pyewacket; Bermuda on Titan; Mac on Genuine Risk. Photo KL

George’s scrapbook: An exultant Psyche crew, 1965. George is far right in the crew photo. Far left in both B&W photos is one of the great navigators of his generation, Ben Mitchell. His son, Ben, is the littlest kid in the B&W at bottom. In a Comment below, Ben writes that he sailed the three milestone races: Transpac on Pyewacket; Bermuda on Titan; Mac on Genuine Risk. Photo KL

With the Centennial approaching, Transpac YC board member and Cal 40 owner Stan Honey (Illusion) put his name and stature behind a push to build up a Cal 40 class.

And there we were, fourteen Cal 40s on the line on a July afternoon at Point Fermin, and it was a mucky day fading into the muckiest night. Our first 24 hour run was 35 miles. Our second was 31 miles. There was a point where I told Fin Beven, owner of hull #24, Radiant, “The good news is, we’re passing the bubbles. The bad news is, I have time to count them.” I wrote then that light air sailing has its challenges, mostly personal: “At its edgiest, light-air sailing opens a window into the character of a man; you can judge whether his potty training went well or ill.”

By the time we got beyond Southern California’s inner coastal waters and deep into the northwesterlies of its outer coastal waters, any thought that an overall winner could come out of our division was done for. It’s a truth that you race your division, and conditions on the course determine the overall winner. Meanwhile, Taylor Pillsbury’s Ralphie had already been positioned far to the south of our track by the boat’s insistent navigator, Don Jesberg. In that, lay the race.

There were good arguments for the “lane” we had chosen as we entered the tradewinds that circulate south of the Pacific High Pressure Zone. The simplest evidence is that we had company from Illusion—Sally Honey and her all-female crew of Melinda Erkelens, Charlie Arms and Liz Baylis. Besides having a high regard for Sally’s own smarts, I have every confidence that she had conferred closely with husband Stan before our start. Stan is on the short-short list for world’s greatest navigator, and that’s enough to validate the big-picture strategy we took with us into the race. And then.

And then the Pacific High began to break up. Our breeze broke up with it. Ralphie was gone like a rabbit on the south side of the course, holding the breeze, and we’d never catch Ralphie now. I hate it when that happens.

So, should we take a left turn, sail laterally across the course, and fall in line to scrap for second? Or hold on where we were, hoping for a major turnaround? The decision was made to stick with our side of the racecourse. Meanwhile, Illusion made the left turn, fell in behind Ralphie, and eventually finished second. My crewmate, Ric Sanders, quipped, “I wonder if my wife knows I’ve spent the last two weeks chasing girls.”

13 days on, Radiant arrives at Diamond Head. Photo (we believe) by Geri Conser

13 days on, Radiant arrives at Diamond Head. Photo (we believe) by Geri Conser

Psyche, the 1-1 winner of the 1965 Transpac, finished as the third Cal 40. Meanwhile, starting six days behind us, with breeze, Hasso Plattner’s cant-keeled maxi, Morning Glory, passed us at sea and made the Diamond Head Buoy in 6 days, 16 hours to set a new course record. Roy Disney’s Pyewacket, navigated by Stan Honey, arrived two and a half hours behind, also ahead of the former record.

The late Roy Disney, I must now say, then with 15 Transpacs behind him and a lifetime of supporting and promoting the race, was 75 years old in 2005. No one on the Board of Transpac YC would ever say to me that any of that factored into the decision to go one year early with the Centennial—Disney had hopes of recapturing his race record—but one might wonder.

For Fin Beven, navigator Charlie Beven, Ric Sanders, David Griffith (George’s son) and little old me, the passage time on Radiant was thirteen days, leading to the big payoff spinnaker run down the Molokai Channel that makes you forget that 35-mile day one.

Silly grins all around. KL, left, Ric Sanders (on tiller), Fin Bevin (right) and David Griffith in the Molokai Channel. Behind the camera, navigator Charlie Beven

Silly grins all around. KL, left, Ric Sanders (on tiller), Fin Bevin (right) and David Griffith in the Molokai Channel. Behind the camera, navigator Charlie Beven

More than 1,100 people gathered in the ballroom of the Ilikai Hotel for the prizegiving, where Disney and I exchanged race tales and he quipped, with a little grin, “I’d love to do this race on a Cal 40, but I just don’t have the time.”

RIP, Roy.

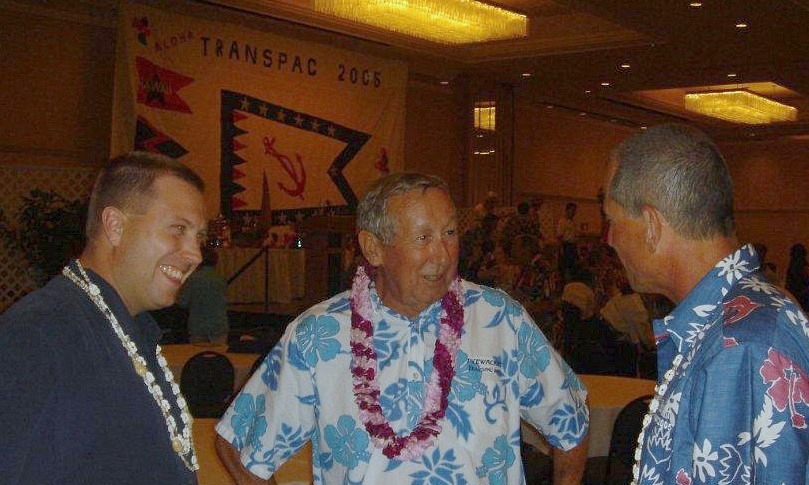

Ian Pinkham, Roy Disney, KL. Centennial Transpac, 2005. Photo by Cole Beven Pinkham

Ian Pinkham, Roy Disney, KL. Centennial Transpac, 2005. Photo by Cole Beven Pinkham

This account will continue, with Bermuda and the Mac, as occasion serves.