Stars at 100

The wildest sailboat ride I ever had was not on a wing-powered catamaran. It was on a “simple” Star.

What Tom Blackaller once told me about sailing in an Olympic Trials on San Francisco Bay—

“It was like going into a fire hose that’s shooting 40 knots.”

and

“I just sailed it under.”

—crossed my mind.

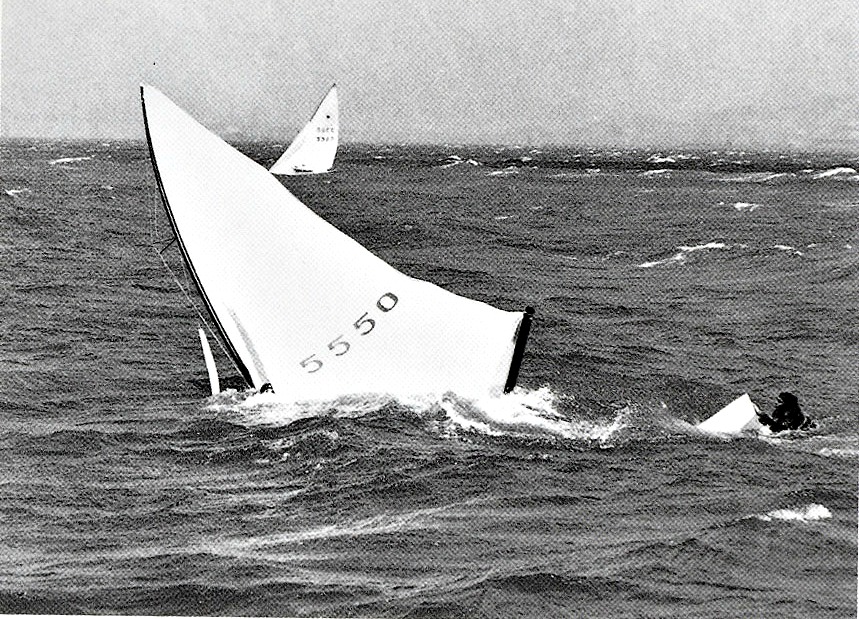

The wind on the final day of the 1972 Star Class trials went way-doggies off the curve, even by the community standards of windy San Francisco Bay. Think 40 knots, gusting to 45. The Olympic Circle was a mass of whitecaps, and yes, despite the best efforts of the man who would become the 1974 and 1980 Star world champion, he “just sailed it under.” There’s a series of classic shots of Blackaller and crewman Bill Munster swimming alongside the soon-to-disappear transom of Star 5550, Good Grief . . .

1972, San Francisco Bay. Source: starclass.org

1972, San Francisco Bay. Source: starclass.org

And there I was in my own time in the crew position for Austin Gibbon, and it was like going into a fire hose that’s shooting 40 knots.

And now it’s 2012 and we have run out of time on 2011, the 100th anniversary of what is not only the oldest surviving one design class, but an original that proved the concept. We forget now that small-boat sailing nosedived in the USA in the early 20th century as internal combustion took off. Allowing for a few successful one-design experiments in Ireland and the UK in the 19th century, the inspiration behind the one-design boat that made a difference in the years to come was one George Corry in the USA. He wrote in 1923, “Small boat sailing is enjoying a boom such as the sport hasn’t known for a quarter of a century. This rejuvenation of a pastime that seemed doomed to extinction with the advent of the automobile and the motorboat has been brought about almost entirely by the development of the one design sailboat, known as the Star Class.”

And now it’s 2012 and we have run out of time on 2011, the 100th anniversary of what is not only the oldest surviving one design class, but an original that proved the concept. We forget now that small-boat sailing nosedived in the USA in the early 20th century as internal combustion took off. Allowing for a few successful one-design experiments in Ireland and the UK in the 19th century, the inspiration behind the one-design boat that made a difference in the years to come was one George Corry in the USA. He wrote in 1923, “Small boat sailing is enjoying a boom such as the sport hasn’t known for a quarter of a century. This rejuvenation of a pastime that seemed doomed to extinction with the advent of the automobile and the motorboat has been brought about almost entirely by the development of the one design sailboat, known as the Star Class.”

Between 1911 and 1923, the Star had already spread from New England to the Gulf of Mexico, the Great Lakes, the Pacific Coast, South America, Australia and New Zealand.

And so, years on, Austin had a Star to drive, and I had a Star to crew, with the mission to deliver said Star from the San Francisco cityfront to Richmond Yacht Club, a downwind ride to the far reach of the bay. A perfect downwind ride, you could say, port gybe all the way, carving a wall of water up both chines. I mean, we couldn’t see out . . .

Sometimes you could peek over . . .

And the breeze was way-doggies off the charts again, fortyish in the gusts, and the bay was ebb-tide green with washboard waves, white on top, and there was a lot of spitting, and a bit of hooting and hollering, and I would have kept my fingers crossed except that wasn’t working for me, and this is intended as an homage to the Star in its 100th year—thank goodness we weren’t racing because a pencil neck like me couldn’t have kept the boat down, upwind—and, fortunately, Richmond is a big target. And, fortunately, we missed Alcatraz, and I guess we could have made it a question when we got to Richmond about whether to gybe or not, but by golly it took hardly any conversation at all to agree to tack around instead and we were plum grateful when that worked because on that day there was no Riviera on the “Richmond Riviera.” Whew. Soaked through. From the outside in, and the inside out.

Even with the Star Class struggling in recent years to maintain its history as the ultimate marriage of elite sailors and weekend warriors, I have looked upon the Star as the window into the question of Who We Are, and is there an Us in this sport. Star Class sailors like to say that their competition is the graduate school of small boat sailing. Where did two-time Laser Gold Medalist Robert Scheidt turn, after the Laser? To the Star, of course. The ISAF decision to drop Stars from the 2016 Olympiad speaks directly to the tension between the vision of Olympic sailing as an expression of our finest traditions, versus, um, television entertainment.

Enough already has been written about that.

And I’m ready to see kites in the Olympics, so just call me conflicted.

Meanwhile, thank you to the Star Class, and thank you to the late Austin Gibbon, for the wildest boatride I ever had.

Austin Gibbon at the helm. Courtesy Barbara Wood

Austin Gibbon at the helm. Courtesy Barbara Wood

And just so we understand each other, below is a more extensive excerpt from George A. Corry’s writings of 1923, first published in Popular Science and reprinted in the Summer 2011 edition of STARLIGHTS. The astute reader will note that I edited Corry’s words above, but not below:

August, 1923

“Small boat sailing and racing this season is enjoying a boom such as the sport hasn’t known for a quarter of a century. This rejuvenation and return to popularity of a pastime that seemed doomed to extinction with the advent of the automobile and the motorboat has been brought about almost entirely by the development of the one design sailboat, known as the Star Class.

“Taurus”, Star #1, sailed by W.L. Inslee, winning the 1922 National Championship for the Western Long Island Sound against

“Taurus”, Star #1, sailed by W.L. Inslee, winning the 1922 National Championship for the Western Long Island Sound against

Stars from the Atlantic, Pacific and Great Lakes. Source: 1923 Log/starclass.org.

“The introduction of the cheap, lightweight gas engine in motor-cars and motor-boats hit small boat sailing hard, and the sport went into a steady decline; then the war came, and sailboat building ceased for three years. The few hardy skippers who stuck to the helm and depended upon natural forces for propelling power in those days were advised to ‘put a kicker in her and get somewhere.’ Nothing but speed seemed to interest this army of ‘scorchers’ and new engine drivers who had only lately tired of the bicycle fad. But even in those days when small boat sailing was at its lowest ebb, there remained a small group of yachtsmen who still were faithful to the call of the ships, and who were held steadfast by the lure of the sea. In 1910 I was able to interest a few members of the American Yacht Club, of Milton Point, Rye, New York, in a project to build a number of small sailboats of the same design with the object of racing among themselves.

“The plan succeeded far beyond my expectations.”

.