William Faulkner, Sailor Man

Being on a Southern sojourn, I counted it high time to renew acquaintance with my friends Eudora Welty, Robert Penn Warren, William Faulkner—

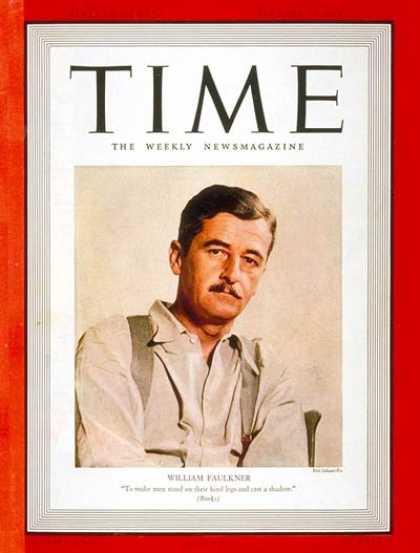

And so it came about that in a five-pounder of an anthology I found a piece by Faulkner that was new to me, an autobiography of sorts in 19 pages posing as an investigation of swamps and Snopses and small towns called cities and tiny black women of fortitude and loyalty who lived and died surrounded by admiration and slow tragedy: out of that welter emerged a few nuggets of the 1949 Nobel Prize Winner from Oxford, Mississippi as a sailor.

Faulkner the sailor? News to me.

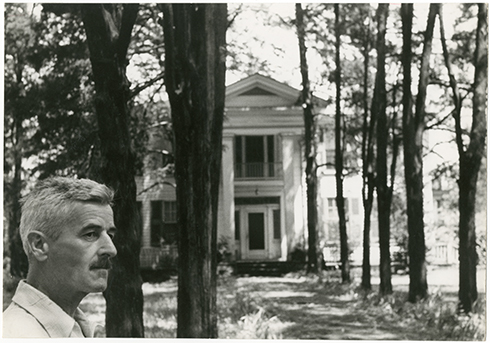

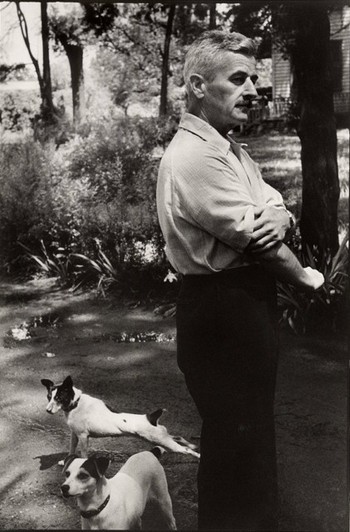

Faulkner at home in Oxford, Mississippi, by Henri Cartier-Bresson

Faulkner at home in Oxford, Mississippi, by Henri Cartier-Bresson

Which set me to thinking , which is always risky, but I’ll find my way back to sailor-talk after I’ve poked at a few random thoughts, such as: I cannot read Faulkner, sailor or otherwise, outside the context of the great struggle of my generation, which was the Civil Rights Movement, which rerouted history and adjusted society but failed to redeem it and led us into a promised land that does not yield the fruit that Martin Luther King imagined. Nor can I read Faulkner outside the context of the great struggles of the 19th century, the War Between the States, remembered by the victors as the Civil War, and the aftermath, and the aftermath of the aftermath, which is where Faulkner found his fertile ground. Against that, it may require an attuned sensitivity to the inherited-white Southern mind to read Faulkner’s words about the aftermath—remembering that, for his denunciations of racism, the man was reviled by the editorial writers of the Jackson Clarion Ledger, who may or may not have been capable of reading him at an adult level—to read Faulkner’s words, that is, and digest those words as we hear him subtly modulating the awkward history of the place in the years after The War, via a white Southern Mind:

Soon he (the Negro) would even forge ahead in that economic rivalry with Snopes which was to send Snopes in droves into the Ku Klux Klan—not the old original one of the war’s chaotic and desperate end which, measured against the desperate times, was at least honest and serious in its desperate aim, but into the later and base one of the twenties whose only kinship to the old one was the old name.

For the alert, the intricacies and trapdoors are fascinating as we approach the 150th anniversary of the war that made us a nation. I figure Mr. Faulkner found it complicated to be a Southern man possessed of a conscience and an independent mind and tremendous, tough love for his flawed Mississippi, early- to mid-century of the 20th, and possessed also of personal pride tinged by collective pride and irreconcilable collective shame, and the word pictures he painted in his life still capture light in deep stabs of a careful brush, exposing the soft decay but also the beauty which is so often a melancholy beauty, and it was always about the land.

For the alert, the intricacies and trapdoors are fascinating as we approach the 150th anniversary of the war that made us a nation. I figure Mr. Faulkner found it complicated to be a Southern man possessed of a conscience and an independent mind and tremendous, tough love for his flawed Mississippi, early- to mid-century of the 20th, and possessed also of personal pride tinged by collective pride and irreconcilable collective shame, and the word pictures he painted in his life still capture light in deep stabs of a careful brush, exposing the soft decay but also the beauty which is so often a melancholy beauty, and it was always about the land.

He did it best in his novels, where the astute reader can taste the extra cup of sour mash flowing into an extra phrase or five or six in a single sentence, the words marching in a line punctuated as the line of Beauregard’s men, bitter on the Corinth Road, or flashing like Forrest’s madcap counterpunch back toward Shiloh. Bloody, bloody Shiloh. But the autobiographical piece that is the source of these excerpts that reveal William Faulkner the sailor is called simply—

MISSISSIPPI

At this time the young man’s attitude was that of most of the other young men in the world who had been around twenty-one years of age in April, 1917, even though at times he did admit to himself that he was possibly using the fact that he had been nineteen on that day as an excuse to follow the avocation he was coming more and more to know would be forever his true one: to be a tramp, a harmless possessionless vagabond.

Thus Faulkner offers an introductory morsel of a self. Then the narrative, labeled an essay, proceeds to examine the land, from the primeval, to the land inhabited by Choctaw and Cherokee, to the white pioneer invasion, to the pioneers’ displacement in turn by “the younger sons of Virginia and Carolina planters coming to replace him in wagons laden with slaves and indigo seedlings over the very roads that he had hacked out with little more than a tomahawk.” Eventually in this essay, with the land in his developing real history of it populated at whim by his fictional Snopeses and Sortorises and De Camps, the South’s most eccentric writer (of significance) turns to a description of a relentless flood of the great river itself, sweeping over farmland and whole villages, swallowing them whole and hauling off farmland wholesale and villages wholesale and bloated cattle and cats and foxes and broken dreams of mended fences, and with them too—and by the way it is widely recognized that it is fatal to other writers to be drawn into the trap of writing in Faulkneresque—the reader is hauled off to the Gulf Coast and a different world.

Thus Faulkner offers an introductory morsel of a self. Then the narrative, labeled an essay, proceeds to examine the land, from the primeval, to the land inhabited by Choctaw and Cherokee, to the white pioneer invasion, to the pioneers’ displacement in turn by “the younger sons of Virginia and Carolina planters coming to replace him in wagons laden with slaves and indigo seedlings over the very roads that he had hacked out with little more than a tomahawk.” Eventually in this essay, with the land in his developing real history of it populated at whim by his fictional Snopeses and Sortorises and De Camps, the South’s most eccentric writer (of significance) turns to a description of a relentless flood of the great river itself, sweeping over farmland and whole villages, swallowing them whole and hauling off farmland wholesale and villages wholesale and bloated cattle and cats and foxes and broken dreams of mended fences, and with them too—and by the way it is widely recognized that it is fatal to other writers to be drawn into the trap of writing in Faulkneresque—the reader is hauled off to the Gulf Coast and a different world.

And:

That was Mississippi too, though a different one from where the child had been bred; the people were Catholics, the Spanish and French blood still showed in the names and faces. But it was not a deep one, if you did not count the sea and the boats on it; a curve of beach, a thin unbroken line of estates and apartment hotels owned and inhabited by Chicago millionaires, standing back to back with another thin line, this time of tenements inhabited by Negroes and whites who ran the boats and worked in the fish-processing plants. Then the Mississippi which the young man knew began: the fading purlieus inhabited by a people whom the young man recognized because their like was in his country too: descendants, heirs at least in spirit, of the tall men, who worked in no factories and farmed no land nor even truck-patches, living not out of the earth but on its denizens: fishing guides and individual professional fishermen, trappers of muskrats and alligator hunters and poachers of deer, the land rising now, once more earth instead of half water, vista-ed and arras-ed with the long leaf pines which northern capital would convert into dollars in Ohio and Indiana . . .

Then, turning his face again to the Gulf Coast, Faulkner writes:

The man remembered from his youth too: one summer spent being blown innocently over in catboats since, born and bred in the North Mississippi hinterland, he did not recognize the edge of a squall until he already had one. The next summer he returned because he found that he liked that much water . . .

He learned the barrier islands too: one of a crew of five amateurs sailing a big sloop in off-shore races, he learned not only how to keep a hull on its keel and moving but how to get it from one place to another and bring it back: so that, a professional now, living in New Orleans he commanded for pay a power launch belonging to a bootlegger (this was the twenties), whose crew consisted of a Negro cook-deckhand-stevedore and the bootlegger’s younger brother: a slim twenty-one or twenty-two year old Italian with yellow eyes like a cat and a silk shirt bulged faintly by an armpit-holstered pistol too small in caliber to have done anything but got them all killed . . .

And much later in this “essay” the setting returns to the hill country of Faulkner’s boyhood—

On his way into town from his home the middleaging (now a professional fiction-writer: who had wanted to remain the tramp and the possessionless vagabond of his young manhood but time and success and the hardening of his arteries had beaten him) man would pass the back yard of a doctor friend whose son was an undergraduate at Harvard. One day the undergraduate stopped him and invited him in and showed him the unfinished hull of a twenty-foot sloop, saying, “When I get her finished, Mr. Bill, I want you to help me sail her.” And each time he passed after that, the undergraduate would repeat: “Remember, Mr. Bill, I want you to help me sail her as soon as I get her in the water,” to which the middleaging would answer as always: Fine, Arthur. Just let me know.”

Then one day he came out of the postoffice: a voice called him from a taxicab, which in small Mississippi towns was any motor car owned by any footloose young man who liked to drive, who decreed himself a taxicab as Napoleon decreed himself an Emperor: in the car with the driver was the undergraduate and a young man whose father had vanished somewhere in the West out of the ruins of the bank of which he had been president, and a fourth young man whose type is universal: the town clown, comedian, whose humor is without viciousness and quite often witty and always funny. “She’s in the water, Mr. Bill,” the undergraduate said. “Are you ready to go now?” And he was, and the sloop was too; the undergraduate had sewn his own sails on his mother’s machine; they worked her out into the lake and got her on course all tight and drawing, when suddenly it seemed to the middleaging that part of him was no longer in the sloop but about ten feet away, looking back at what he saw: a Harvard undergraduate, a taxidriver, the son of an absconded banker and a village clown and a middleaged novelist sailing a home-made boat on an artificial lake in the depths of the North Mississippi hills: And he thought—

That was something which did not happen to you more than once in your life.

A blue heron on watch at Sardis Lake, Mississippi. Source: Wikipedia

A blue heron on watch at Sardis Lake, Mississippi. Source: Wikipedia

Most probably, the unnamed lake where Faulkner sailed with his young companions was Sardis Lake, where he joined with friends to build a houseboat in the 1940s. As explained below in a comment from Mississippi-based reader Charles Bond—read the comment, it adds immeasurably—Faulkner would eventually become the owner of this same little sloop, which he renamed Ring Dove. Eudora Welty, a Jackson lady who could balance words on the head of a pin, sailed there in those days in company with the man disregarded about his home town in his own time as Count NoCount.

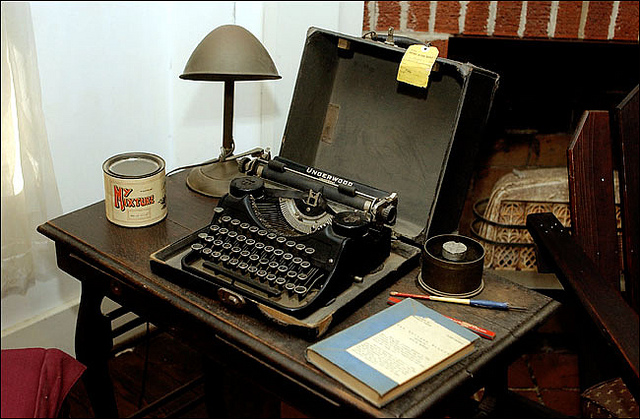

Source: FAULKNER – A Biography, by Joseph Blotner: 1974

Source: FAULKNER – A Biography, by Joseph Blotner: 1974

Sadly, but understandably, there was no room in the Yoknapatawpha County of Faulkner’s construction for lifts and headers on a rippling lake. There was no place in his tense microcosm for the grace of sail. Perhaps if he’d had a few more generations to work with, but then, the transformation of the fiction would have to have been as remarkable as the transformation of the reality. In the 21st Century, Oxford, Mississippi is a very cool place.

MISSISSIPPI copyright 1954 by the Curtis Publishing Company

AND THEN

And then I returned from my Southern sojourn in time to catch the pink rays of sunset over the Golden Gate and wonder just what had gone down in the hearings that I missed at the San Francisco Planning Commission and Port Commission regarding the critical EIR for America’s Cup 34.

The short answer: An all-up vote in favor on both counts. The less-short answer: There are opponents, though not necessarily opponents that spell catastrophe for the event. In some cases, it’s all about politics and pulling the shades to ask, “OK, what is it you really want?”

C.W. Nevius, columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle, has already covered that ground, and he put it this way.